Now, Temer is politically very far to the right of Dilma – who was once hailed as the heiress to the very popular political legacy of Lula da Silva but has then mismanaged the economy badly to lose popularity. Temer is accused of serious corruption and is probably correctly described as allied with the right wing forces (equally or worse corrupt) of parliament that want to have Dilma removed. This fact, together with a truly crazy roller coaster process of parliamentary decisions, courts and judges interfering at different levels, and a fresh speaker of parliament trying a last minute nullification of the whole shebang the other day, then making a 180° turn just a few hours later, have made commentators to the left side of typical conservative politics talk about a "coup". Not a military coup or a palace coup, of course, but nevertheless something truly undemocratic and fishy going on to remove a democratically elected political leader to the benefit of one representing a party that has performed weak to say the least in the last few general elections. This, not least, is Dilma's own main line. Some sources describing the same or very similar points are here, here, here, here, to name just a few. What's so interesting with this argument is that those who sing the coup line, do it with a long line of qualifiers. It's a "soft" coup, or a "light" one, it's not unconstitutional, but still a coup, neither is it against the democratic process of Brazil, but a coup nevertheless. And so on. So, one may wonder, with that definition of a coup, what's not a coup in the area of democratic states changing leaders?

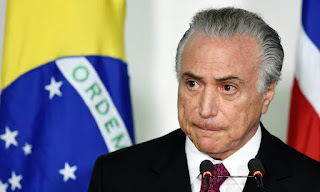

Let's face it. Brazil is a constitutional democracy. One might prefer changes to its constitution, but that goes, of course, for all constitutional democracies. None of them are perfect. Within this constitution, Dilma has been elected for president by (strong!) popular vote, and it seems that none of the coup advocates complain about that, so Brazil democracy must be doing OK also by their light. Likewise, within this constitution, Dilma has selected Michel Temer as her vice prez, probably for reasons of the power politics of forming political alliances going on in any democratic state following a general election. That is, Michel Temer is as democratically selected as any vice president or vice PM of any country. Moreover, the role of a vice prez or PM is exactly to step in when the president or PM cannot perform their duties of office. This, once again, does not make Brazil an exception from other constitutional democracies. This alone settles the fact that there is nothing undemocratic or constitutionally dodgy of having a political mirror image taking over for Dilma. It's a consequence of her own democratic political moves to form a strong government to lead. This holds whatever the reason for her incapacity to execute her office, should it be illness, disappearance, death – or criminal charges. Moreover, the impeachment process seems to be perfectly constitutional, as the democratic constitution here gives the power to drive it to parliament rather than courts. Again, this may look unsatisfactory to some, but this solution to the issue of how to deal with (suspected) criminal political leaders, is far from unique among constitutional democracies around the world. At the end of the day, therefore, the 180 day removal of Dilma from office seems to be perfectly democratic and constitutional, and the consequence of this removal is that Temer now takes over, again (as we saw) perfectly in line with constitutional democratic rules and procedures.

My conclusion is that if the removal of Dilma and insertion of Temer as president is a coup, so is every constitutionally democratic (re)formation of government all over the world.

What we see in Brazil is nothing undemocratic or even a lack of democracy. It is about a deeply corrupt state and country, where political leaders sell themselves for money and form ideologically bizarre alliances for the mere reason of holding on to power, and the country's highest leader making serious political mistakes and not revising policies. This is something that needs to be highlighted much more: democracy is no guarantee for sound politics or well functioning states. It has other merits, of course, but to get at the deficiencies exposed by the latest mess in Brazil, we should look in other directions than the system for allocating formal political power, namely here.

***